About those postponed “elective” surgeries we were told were just gravy for greedy doctors: NY State doctors could re-classify needed pancreatic cancer surgery as “elective” by instead offering patients chemo to tide them over during NY State order barring “elective surgeries statewide to ensure beds were available for COVID-19 patients.”…Closure of many physicians’ offices also prevented timely care…”On Wednesday [Nov. 3], there were 592 inpatients, more than the 583 inpatient room beds, Schwarz said. All but eight were non-COVID-19 cases.”

11/7/21, “Long Island hospitals seeing uptick in seriously ill patients, but not for COVID-19," Newsday, David Olson

“Some Long Island hospitals are seeing an uptick in seriously ill patients, and patient deaths, a trend doctors said may stem largely from people delaying care for fear of contracting the coronavirus.

“Some Long Island hospitals are seeing an uptick in seriously ill patients, and patient deaths, a trend doctors said may stem largely from people delaying care for fear of contracting the coronavirus.

“Our patients now are sicker than our patients used to be,” said Dr. Richard Schwarz, medical director of Long Island Jewish Medical Center in New Hyde Park, which in the past two months has regularly been over capacity. “The people in the ICU [intensive care unit] are staying there longer than before, and some of the outcomes are not as good.”

Hospitals on Long Island are seeing an increase in seriously ill patients and deaths from what they believe is partly a result of people delaying care because of the pandemic.

Studies and surveys have found that many people avoided doctors because they were afraid of contracting the coronavirus, or that

they couldn’t get appointments because of closed offices.

When people put off going to the doctor, conditions can worsen and become irreversible and potentially fatal, doctors say….

Hospitals statewide are seeing a higher-than-usual number of patients in inpatient beds and in emergency rooms, said Bea Grause, president of the Healthcare Association of New York State, which represents nonprofit hospitals and health care organizations.

Although there’s no data to document how much of the increase is due to people who put off care, “It’s reasonable to connect pandemic-related delays to at least some of the current influx,” Grause said in an email.

Dr. Shaline Rao, a cardiologist at NYU Langone Hospital-Long Island in Mineola, said she’s seen a larger share of her patients die since the pandemic began than is typical.

“I thought they had potential to stabilize or even recover, but they didn’t come in and they didn’t follow up as I had hoped,” said Rao, director of advanced cardiac therapeutics for the hospital. “Then we find out they passed away.”

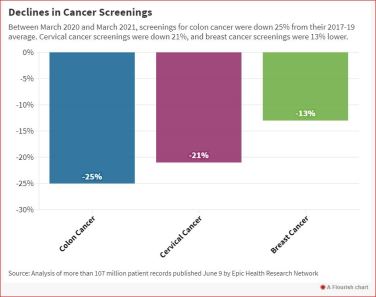

Forty-one percent of Americans said they had forgone medical care from March to mid-July 2020, a survey published in January in JAMA Network Open found. Fear of contracting COVID-19 and closed outpatient medical practices were the main reasons, according to the survey. During the spring 2020 COVID-19 peak in New York, health systems across Long Island sent doctors, nurses and other staff from outpatient offices to hospitals to handle the crush of COVID-19 patients there.[Dr. Richard] Schwarz, [medical director of Long Island Jewish Medical Center in New Hyde Park] said even with many doctors and nurses focused on COVID-19 patients during the early weeks of the pandemic rather than on their regular patients, “Things that were felt to require urgent attention got it. Things that did not seem so urgent were delayed. But any time you’re dealing with any medical condition, delay is not your friend.”…

In addition, doctors did not want to unnecessarily expose to the coronavirus medically vulnerable patients who did not appear to urgently need care, he said.

Hospitals throughout the Northwell Health system — of which Long Island Jewish is a part — are noting that patients in recent weeks appear to be on average sicker than usual, said Dr. David Battinelli, a senior vice president at Northwell Health.

The same is true in emergency rooms across Long Island and the Hudson Valley, some of which also have an unusually high number of patients, said Darwell, whose organization represents 51 Long Island and Hudson Valley hospitals.

At Long Island Jewish, “We’ve consistently gotten more patients than we have room for” in inpatient rooms over the past two months, Schwarz said. Some patients must wait for inpatient beds on stretchers in the emergency department, with staff and portable equipment monitoring them there, he said.

One reason for the higher patient census is that because patients are on average sicker, they’re staying in the hospital longer, he said.

“We think people are coming in with the same diagnoses, but at a more advanced stage,“ he said.

On Wednesday [Nov. 3], there were 592 inpatients, more than the 583 inpatient room beds, Schwarz said. All but eight were non-COVID-19 cases.

All 48 intensive care beds are sometimes full, so “we’ve been using overflow beds, beds that are not typically ICU beds,“ Schwarz said.

“I now have a daily call with all of the medical directors of all of our intensive care units basically trying to juggle beds and see who we can put where,” he said.

Checkups, screenings can make a difference

Dr. Aaron Glatt, chairman of medicine at Mount Sinai South Nassau hospital in Oceanside, said that with certain diseases, a checkup or screening could spell the difference between successful early treatment and serious disease.

“It could go from being much more treatable, to much less treatable, and even sometimes fatal,” he said.

[Dr. Shaline] Rao, [a cardiologist at NYU Langone Hospital-Long Island in Mineola] said primary care doctors typically are the first to spot a potential cardiac-related problem, and they then refer patients to cardiologists. Skipped doctor appointments mean a potential heart condition could remain undiagnosed and untreated, she said.

If an issue is first diagnosed in a hospital rather than a doctor’s office, “That usually means they’ve already gotten to a phase in which the stress of the high blood pressure has resulted in heart or kidney dysfunction or potentially even a stroke,” she said. “It’s much harder to guarantee the type of reversal or improvement that we get when we treat people much earlier, in the office.”

Rao said some cardiac patients still are nervous about in-person appointments, because they realize heart conditions make them more susceptible to severe COVID-19. But, she said, doctors’ offices and hospitals have extensive safety precautions, and “the risk of transmission is much higher just from day-to-day life in the community.”

Concerns about coronavirus transmission within hospitals were higher at the beginning of the pandemic. Pat Rella, a social worker from Little Neck, Queens, said that’s one reason why her doctors at Long Island Jewish waited to schedule her pancreatic-cancer surgery until after the spring 2020 COVID-19 surge. Instead, they put her on chemotherapy while closely monitoring her tumor.

Rella, who is in her 70s, said she “was extremely nervous about” being in a hospital with COVID-19 patients.

“On the other hand, I was concerned that the delay might negatively impact my outcome,” she said.

Rella said doctors believed that, with the pre-surgery chemotherapy option, her operation would be considered elective, and a state directive temporarily barred elective surgeries statewide to ensure beds were available for COVID-19 patients.

The chemotherapy worked as hoped. “By the time he did the surgery, my tumor had shrunk,” Rella said.

The pandemic also impacted psychiatric care, said Dr. Grace Ting, deputy chief medical officer at Nassau University Medical Center in East Meadow. Many patients skipped appointments, so psychiatrists and social workers weren’t seeing issues that could have been addressed through admission to NUMC’s psychiatric floors, which saw the number of new patients plummet during the early months of the pandemic, she said.

Now there often are patients waiting in beds in NUMC’s psychiatric emergency department awaiting one of the 125 psychiatric inpatient beds, Ting said.

Many of the psychiatric inpatient admissions occur after a family member persuades a loved one to seek treatment or reaches out to a psychiatrist, social worker or the police, she said. Throughout much of 2020, when many people isolated themselves, if someone had psychiatric issues, “They were not noticed,” she said.

“People are going out more now, and family are visiting each other now, so other people are noticing: ‘Hey, this [person] is not acting normally.’””

............

No comments:

Post a Comment