“What’s more, “Caliphate” won a Peabody Award—though the series description provided by the New York Times to the awards makes no mention whatsoever of this struggle for the truth.”

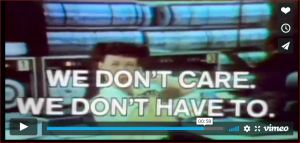

Like the phone company, they don’t care. They don’t have to. They’re the NY Times.

Like the phone company, they don’t care. They don’t have to. They’re the NY Times.

9/28/29, “Subject of NYT ‘Caliphate’ podcast series charged with perpetrating a hoax," Washington Post, Eric Wemple, Media Critic, opinion

“The charge stems from numerous media interviews where the accused, Shehroze Chaudhry, a 25-year-old from Burlington, Ontario, claimed he travelled to Syria in 2016 to join the terrorist group ISIS and committed acts of terrorism,” noted the release.

According to a report by Stewart Bell of Global News, Chaudhry is the actual name of a man identified on the New York Times “Caliphate” podcast series in 2018 as former Islamic State trainee “Abu Huzayfah.” In Chapter 5 of the podcast, for example, Abu Huzayfah describes killing a man in an “orange jumpsuit.” “The blood was just — it was warm, and it sprayed everywhere….I had to stab him multiple times. And then we put him up on a cross. And I had to leave the dagger in his heart,” Abu Huzayfah tells Rukmini Callimachi, a star New York Times reporter who specialized in covering the Islamic State and collaborated with producer Andy Mills and several other journalists on “Caliphate.”

The RCMP release said that Chaudhry’s remarks were aired on “multiple media outlets” and caused “public safety concerns” for Canadians. At the time that “Caliphate” was playing Abu Huzayfah’s colorful recollections — in May 2018 — Conservative House of Commons leader Candice Bergen asked, “This guy is apparently in Toronto. Canadians deserve more answers from this government. Why aren’t they doing something about this despicable animal that’s walking around the country?” she said.

Chaudhry’s arrest merely refreshes pressure on the New York Times regarding its handling of “Caliphate.” As the podcast rolled out in weekly installments, discrepancies arose between what Abu Huzayfah told Callimachi and what he told Canadian media. “Did former Canadian ISIS member lie to the New York Times or to CBC News?” asked a CBC News headline from May 19, 2018. Canadian Broadcasting Corp. had interviewed Abu Huzayfah eight months earlier, and the alleged Islamic State fighter offered a less gory picture of his time with the Islamic State, saying he served in a quasi-police squad. “We would enforce dress codes, ensure people don’t smoke, use alcohol or drugs and that men and women didn’t mix,” he told CBC News.

The same guy who told Callimachi about stabbing a man in the heart told Canadian outlet Global News he didn’t kill anyone.

A look at the timeline:

*November 2016: Callimachi interviews Abu Huzayfah saves the material for future use. Her interviews and communications with the alleged Islamic State fighter continue over the coming months.

*September 2017: CBC News publishes interview with Abu Huzayfah, who discusses his work enforcing sharia law for the Islamic State.

*April 2018: New York Times announces launch of “Caliphate,” a multi-episode extension of Callimachi’s reportorial franchise. The series’ prologue ends with some provocative quotes from Abu Huzayfah, including his recollection of what Islamic State leaders had told trainees about killing: “They said, ‘First time, it’s gonna affect you a lot. You’re gonna be sad. You’re gonna be sick. And you might even faint from the blood.’ … But, what you have to do is, you just have to drink down those emotions. Remember you are doing this for God.” The first five episodes revolve around Abu Huzayfah’s claims.

*May 11, 2018: CBC News publishes story stemming from the details revealed in “Caliphate.” Asked whether he’d killed anyone, Abu Huzayfah responded, “I did not. You can put me through a polygraph and it will prove that I didn’t kill anyone.” As to why he indicated otherwise to Callimachi, he said: “I was being childish. I was describing what I saw and basically, I was close enough to think it was me.” New York Times spokeswoman Danielle Rhoades Ha issued this statement to CBC News: “Forthcoming episodes in our series detail the fact-checking process at length and show what we know to be true about his story, and how we came to know it.”

*May 18, 2018: CBC News publishes Callimachi’s comments about the discrepancy. She says that the Times has been able to verify the “scaffolding” of Abu Huzayfah’s story. Just hours after Abu Huzayfah’s first interview with the Times, says Callimachi, Canadian authorities approached him — meaning that the newspaper got to him “in this window of time when he essentially thought he had slipped through the cracks,” said Callimachi. The implication here is that the Times may have caught Abu Huzayfah in a moment of peak candor.

*May 24, 2018: The Times publishes its sixth episode in the “Caliphate” series, titled “Paper Trail” — essentially a fact-checking exercise. It discloses that Callimachi & Co. had found a problem with Abu Huzayfah’s timeline, exposing a lie that he had told in his interviews with the Times. The effort also pulls in three top reporters at the Times who tell Callimachi that Abu Huzayfah was on a no-fly list and that according to two U.S. officials, he was a “member of ISIS.” It’s unclear, however, whether the sources for these revelations were merely regurgitating Abu Huzayfah’s own confession to CBC News that he had joined the Islamic State.

Via geo-web wizardry, the Times also managed to secure a photo of Abu Huzayfah on the banks of the Euphrates River in Syria, an indication that he’d made the trip.

What to make of all these details, conflicting accounts and timelines? One takeaway is that reporting on the Islamic State is one of the industry’s near-impossible feats. For years, globe-trotting correspondents with major Western news organizations have attempted to track down Islamic State fighters who have left the battlefield and retreated to their homelands. Nailing down their accounts requires years of sourcing, luck and a reportorial sixth sense. “In years of interviewing IS suspects from Iraq and Syria, it’s rare that they would ever admit to committing gratuitous crimes,” a Middle East correspondent tells the Erik Wemple Blog. “I’ve never had anyone who said they’ve beheaded someone or were splattered in blood because they realize what’s at risk for them still.”

Near the beginning of her podcast series, Callimachi herself nodded at these very limitations. Confessing that she’d been “frustrated” with her interviewees, Callimachi explained: “The overwhelming pattern is that they’ll have witnessed an execution. They’ll have witnessed a beheading. They’ll have been present when a stoning took place. … But they never took part in it themselves.” In Abu Huzayfah, Callimachi had someone who’d perpetrated two executions.

Or so he said. We asked the Times for comment on the charge against Abu Huzayfah for allegedly hoaxing his past as a terrorist. “Part of what the series explored was whether Abu Huzayfah’s account was true,” responded Ha. “In Chapter 6 the podcast confirms that Huzayfah was lying to The Times about the dates of his travel to Syria, and the timeline of his radicalization. The episode tells listeners what our journalists knew for sure and what was still unknown. In the episode, our staff was able to place Huzayfah on the banks of the Euphrates river in Syria by geolocating his whereabouts in a photo.”

In response to further questions, Ha said in a statement, “The uncertainty about Abu Huzayfah’s story is central to every episode of Caliphate that featured him.” After news of the charge surfaced on Friday, Callimachi tweeted a similar sentiment in a thread on the developments: “Big news out of Canada: Abu Huzayfah has been arrested on a terrorist ‘hoax’ charge. The narrative tension of our podcast ‘Caliphate’ is the question of whether his account is true,” wrote Callimachi, in part.

We dissent. The first five episodes of the series, by and large, recount Abu Huzayfah’s story with minimal skepticism from the host. In Chapter 1, for example, Callimachi does express concern that this fellow may be a “fake”; in Chapter 2, she says she must determine if he’s “for real.”

As the narrative plods onward, however, the listener is licensed to conclude that Callimachi believes he is indeed for real. The validation arrives via Callimachi’s deep awareness of all things Islamic State: When Abu Huzayfah explains some wrinkles in his story, the host jumps in to declare that they track with her reporting. Here, for instance, is Callimachi summing up Abu Huzayfah’s upbringing: “In many ways, his background is typical to so many others that I have spoken to. He was neither rich nor poor. He was from, basically, a middle-class background. He loved video games, ‘Star Wars,’ ” she said. After hearing Abu Huzayfah explain the bureaucracy that greeted him in Islamic State territory, Callimachi proclaimed, “The things that Huzayfah describes? I’ve seen these forms. I’ve held them in my own hands.”

At one point, Abu Huzayfah describes the blood that stained his clothes, the mess of an execution. Callimachi: “It very much jibes with the other accounts I have heard of what these punishments are like, down to the technical details of how they’re carried out — the physical force that it takes to do it, the fact that the person executing the sentence is getting bloodied in addition to the prisoner.” And Callimachi comes away impressed with how Abu Huzayfah describes a group of men who had antagonized the Islamic State. “He properly identifies the crime that ISIS assigns to this group, and he’s using the correct theological terms to refer to them,” she says. “And that’s something that is pretty in the weeds, right? Really specific. In addition to that, he says that leaders of the tribe were also kidnapped and taken back to Syria, and this is something that suggests insider knowledge.”

Snippet after snippet, Callimachi heaped credibility on Abu Huzayfah. Far from amping up “narrative tension,” she drained it. An indication thereof comes from Canadian Parliament, where Bergen called Abu Huzayfah an “animal” — not a liar or confused young man who told conflicting stories to different news outlets.

What’s more, “Caliphate” won a Peabody Award — though the series description provided by the New York Times to the awards makes no mention whatsoever of this struggle for the truth:

“In the war on terror, who are we really fighting? ‘Caliphate,’ the first narrative audio series from The New York Times, follows reporter Rukmini Callimachi on her quest to understand ISIS. Told over the course of one year in 11 cinematic episodes, ‘Caliphate’ marries the new journalism of podcasting — stories told with sound design, musical scoring and high production values — with traditional boots-on-the-ground journalism. The series begins in a hotel room somewhere in Canada, where Callimachi and audio producer Andy Mills meet with a former ISIS member, Abu Huzayfah. Callimachi has been covering terrorism for years. Never had she talked with a recruit who had so recently returned home and had not yet been discovered by authorities. And as their conversation unfolds, it becomes clear how rare this interview is. He begins to tell the story of how he — a Canadian kid from a suburban, middle-class family — left his home, slipped over the Turkish border into Syria and pledged his loyalty to the Islamic State. Huzayfah describes the group’s inner workings as he learns how to use an AK-47, how to enforce religious law, how to physically punish offenders and, eventually, how to kill for the Islamic State. Eventually, he arrives at his breaking point, the moment when, grappling with the atrocities he committed, he decides to escape. Through Huzayfah’s eyes, we witness the pull of revolution. But it’s only when Callimachi and Mills travel to Iraq that the full scope of that revolution comes into focus. Arriving in war-torn Mosul, they see a city destroyed: homes reduced to rubble, corpses strewn in schoolyards. They capture it all on tape. By scouring buildings that ISIS recently abandoned, they discover troves of the terror group’s internal documents — receipts, memos, handbooks, court judgments — that they painstakingly piece together to create a detailed portrait of how the terror state actually worked. While ‘Caliphate’ explores theology and politics, it also includes piercingly human moments that bring home the horrors of war. A Yazidi girl enslaved by ISIS fighters recounts her torture. A militant’s mother weeps for her son. These voices, woven together into a sweeping, immersive audio story, gives listeners an unprecedented view into the world of people who kill for their beliefs, and the long shadow of trauma they leave behind.” — 2018 Peabody Awards entry form.”

The hoaxing charge is problematic for Callimachi and the Times because of what it rules out. After years of investigating Abu Huzayfah, Canadian authorities apparently couldn’t stand up the claims of terrorist activity that he’d made in “Caliphate” and in other interviews. The Canadian criminal code prohibits traveling with the purpose of facilitating or participating in terrorist activities, so the conduct that the state failed to document appears quite broad. “If they had reason to believe that he traveled there with the purpose to participate in terrorist activities, they’d have real difficulties proving the offense that they are now charging him with,” notes Leah West, a lecturer on national security at Carleton University.

Abu Huzayfah is scheduled to appear in court on Nov. 16 — plenty of time for top editors at the Times to consider how to respond if the proceedings further shred his various stories. One thing appears certain: Standing behind some fact-checking effort that arrives at episode No. 6 won’t cut it. Asked about the journalism behind “Caliphate,” West said: “I have a lot of respect for Rukmini as a journalist and an investigative reporter but I do think that — not just the Times — a lot of outlets capitalize on the sensational aspects of ISIS and what they did.”

No comments:

Post a Comment