“Life on the [sugar] plantations was extremely hard with a third of newly imported slaves dying within three years."...The “London, Sugar and Slavery” permanent exhibition “documents how British involvement in slavery came about because of the growing consumption of tea and coffee. …This meant an increased need for sugar, and for cheap labor on colonial sugar cane plantations. On display is a tall collar with long spikes that slaves were forced to wear so that they would snag among the trees if they tried to escape.”...Britain dispatched about 10,000 voyages to Africa for slaves” over a period 245 years beginning in 1562 during the reign of Elizabeth 1...."By the mid-1700s there were approximately 15,000 black servants-many of them slaves-in London."

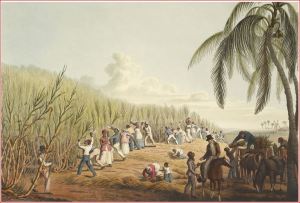

[Image, British sugar slaves: “Enslaved people cutting sugarcane on the Caribbean island of Antigua, aquatint from Ten Views of the Island of Antigua by William Clark, 1832. The British Library”]

[Image, British sugar slaves: “Enslaved people cutting sugarcane on the Caribbean island of Antigua, aquatint from Ten Views of the Island of Antigua by William Clark, 1832. The British Library”]

June 13, 2014, “London’s Legacy in the Slave Trade,” NY Times, Akhil Sharma

“It was a bright Saturday morning, and the City of London, the financial district of the British capital, was empty. I was wandering its narrow side lanes seeking a sculpture….Finally, in a courtyard between office buildings I came upon it: “The Gilt of Cain,” by Michael Visocchi and Lemn Sissay.

A stone pulpit inscribed with a poem is flanked by a dozen tall abstracted figures — a slave auction in progress. It is one of the few memorials to slavery in the city, a shocking fact considering how deeply involved London was in the international slave trade and how many slaves it had been home to over the years, until national abolition in 1833. [It wasn’t until 1838 that slavery was abolished in British Caribbean colonies].

Though it’s much less widely discussed than its American counterpart, London’s relationship to slavery is profound: The city financed and regulated the trade, and the government seated there sent out its navy to protect its shipping routes. In the 1710s and ’20s alone, British ships carried 200,000 slaves across the Atlantic. And, over the centuries, the trade led to a substantial African population in the capital. Even in 1596 their presence was so noticeable that Queen Elizabeth I ordered them to be expelled. Yet their presence only grew as the trade increased. Historians estimate that by the mid-1700s there were approximately 15,000 black servants — many of them slaves — in London, out of a population of around 700,000. Slavery there was as brutal as it was in Mississippi or Alabama; slaves were often beaten so badly that they died or became crippled.

[““The formation of the City of London was shaped significantly by sugar,” said Nick Draper, one of the lead researchers on University College London’s groundbreaking Legacies of British Slave Ownership project. “Merchants in London would advance credit to planters and guarantee remittances to slave traders so that London merchant houses became the center of this economic system built on Caribbean slavery.”" Bloomberg]

Slaves also became part of the city’s visual iconography. Crowds of civilians would watch army bands with slave members playing music influenced by their African background. Bakeries selling sweet treats often had Africans on their signage, as slavery was inextricably linked to sugar cane plantations. Many lanes and streets had names like Black Boy Lane and Blackmoor Alley.

I was in London to explore this complicated, layered legacy. The best place to begin such an overview is probably the old sugar warehouses on the West India Docks. These massive brick buildings along the Thames near Canary Wharf still have windows with thick ominous bars, used to prevent theft when sugar was precious. Today the warehouses contain shops, bars and restaurants, as well as a festive atmosphere; out front, buskers and children with painted faces share the sidewalk. During my visit, a man offered to show me how to ride a unicycle.

But inside one of the warehouses is a site with a darker mood: the Museum of London Docklands and its permanent exhibition on the slave trade, called “London, Sugar and Slavery,” It documents how British involvement in slavery came about because of the growing consumption of tea and coffee. This meant an increased need for sugar, and for cheap labor on colonial sugar cane plantations. The exhibition shows how sugar was produced and then sold in tall cones. On display is a tall collar with long spikes that slaves were forced to wear so that they would snag among the trees if they tried to escape.

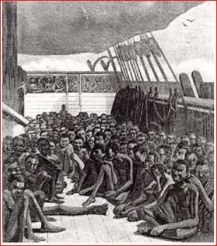

[“Life on the [sugar] plantations was extremely hard with a third of newly imported slaves dying within three years. This created a constant demand for new slaves to replace them.”…“The sugar colonies were Britain’s most valuable colonies….Between 1750 and 1780, about 70% of the [UK] government’s total income came from taxes on goods from its colonies.…The Caribbean islands became the hub of the British Empire....Britain dispatched about 10,000 voyages to Africa for slaves” over a period 245 years beginning in 1562 during the reign of Elizabeth 1….Slave Trade was the richest part of Britain’s trade in the 18th century.”…“British Involvement in the Transatlantic Slave Trade,” The Abolition Project…[Image: African slaves on British ship,

The most chilling feature, though, is an understated wall with a chart that lists the ships that sailed from London. The column headings include the name of ships, their captains, the date the ships left London, their destination in Africa and the number of enslaved Africans they carried from there. I looked at each row of information and thought of how many lives and families had been shattered by the voyage described….

In 1783, Guildhall was the site of the infamous Zong Massacre trial. The Zong was a ship manned by slave traders; they decided to tie the hands and feet of 133 slaves and throw them overboard, and then tried to collect insurance on their dead cargo. When this horror began to be widely known, it pushed many who had been ambivalent about slavery to oppose it. The case was heard by William Murray, Lord Chief Justice and First Earl of Mansfield. A decade earlier, Murray had also been the judge who tried the Somerset case, an ambiguous decision that involved an escaped slave and colonial law and has been interpreted by some as a statement that slavery was unlawful in Britain….

It is easy to stand in the hushed and dignified National Portrait Gallery and think that slavery was brought to a close by elites writing letters to newspapers and giving speeches. Visiting the Parliamentary Archives creates a completely different, and more realistic, understanding: Abolition occurred only when the people in power became afraid of losing their seats in Parliament. Having made an appointment online, I visited the archive, slipping past tourists waiting in long lines and entering Parliament where workers do….

Melanie Unwin, the deputy curator of the Palace of Westminster Collection and one of the organizers of an exhibition on the ending of the slave trade that was held throughout London in 2007,..told me how few Londoners know about the history of slavery in their own city. “Most would be surprised that there were blacks in the U.K. before the 1950s.” I had noted this surprising fact myself in conversations with white Britons — although everyone I spoke to did want to learn more.”…

……………………………………………………..

“Editors’ Note: After this article was published, editors learned that the writer had accepted free accommodations from the hotel that is mentioned. Times policy does not allow travel writers to accept such benefits; if editors had known in advance about the arrangement, the article would not have been published.”

…………………………………..

Added: Slave voyage estimates

Trans-Atlantic Slave trade estimates, 1501-1866

No comments:

Post a Comment